The Perfect English Faculty

The perfect English faculty can be found at Moonwater Park School, which is located in a small town in the South West of England.

As 11-16 comprehensives go, you could describe it as average, in terms of PP intake and percentage of SEN pupils – which were both around national average – and its Progress 8 measure, which last year was a smidgen above 0 (although the English results dug them out of a hole there). In the nicest possible way, you could call it a bog standard comp.

So how come I’m using the word ‘perfect’ to describe its English department? Well, I can see some of you raising your eyebrows at my choice of adjective. Some will dislike the connotations of the word, with its suggestion that it can’t be improved. What’s more, if I spoke to Erica – the Head of Faculty – and Julia – Second in Faculty – about this, I’m sure they wouldn’t like the term either. Especially given that 4 or 5 years ago the English faculty at Moonwater Park was really struggling, with an absence of leadership, low morale among the English staff, and poor pupil outcomes in the subject. But now I think it really is perfect. In my eyes. It’s a place that should inspire us all. A faculty that we might all try and emulate. Every time I come back from visiting I’m bursting with ideas. And bursting with pie. They do a mean chicken and ham in the canteen on a Thursday.

What then makes this humble little department so special? What makes them stand out from the crowd? What’s their secret to exam results that would have most headteachers salivating, the way that I’m salivating now thinking about that pie?

The rest of this talk will involve me outlining the ten characteristics that make Moonwater Park’s English faculty so good. And along the way, I’ll hopefully tell the story of how they went from being a faculty in crisis to a team at the very top of their game.

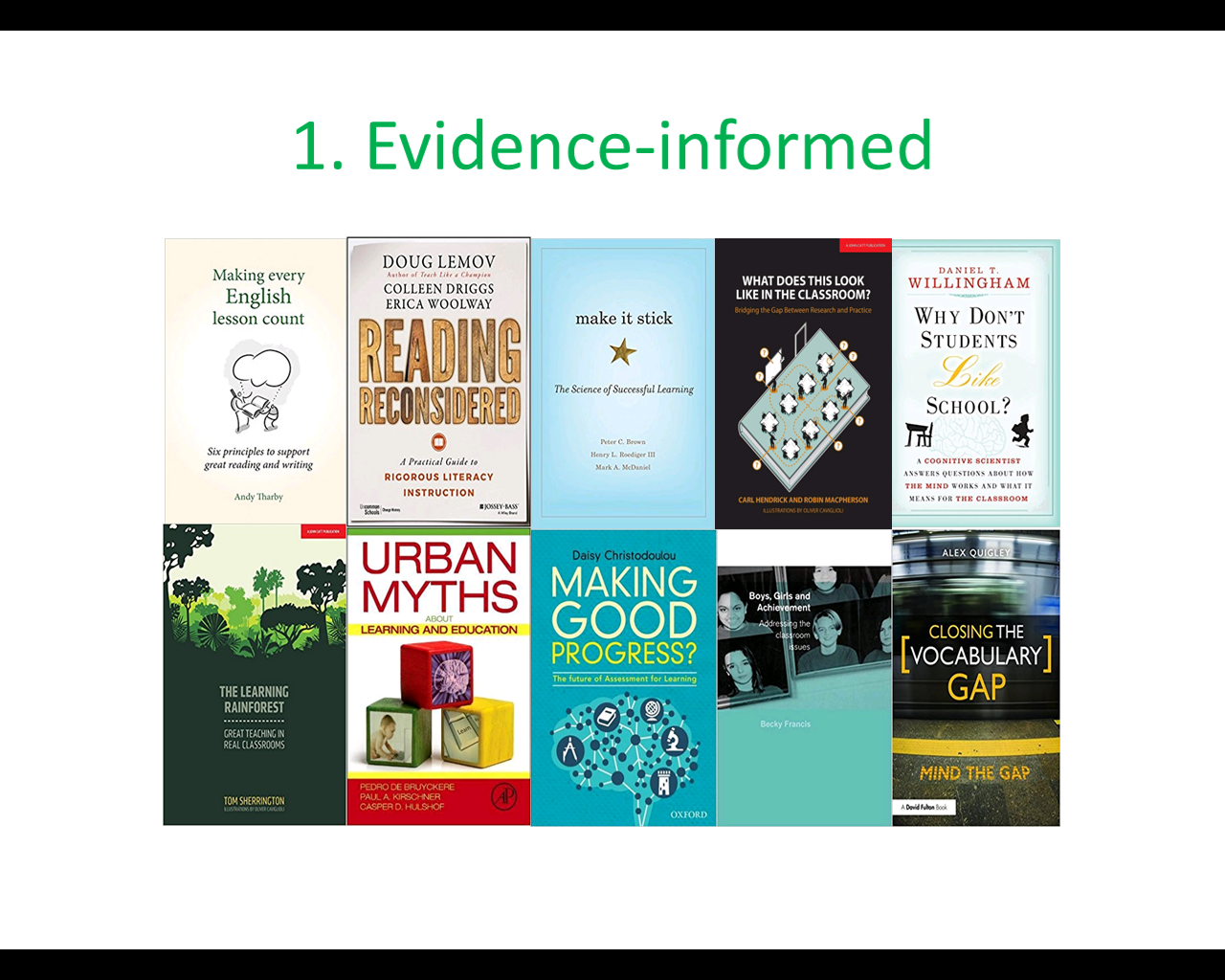

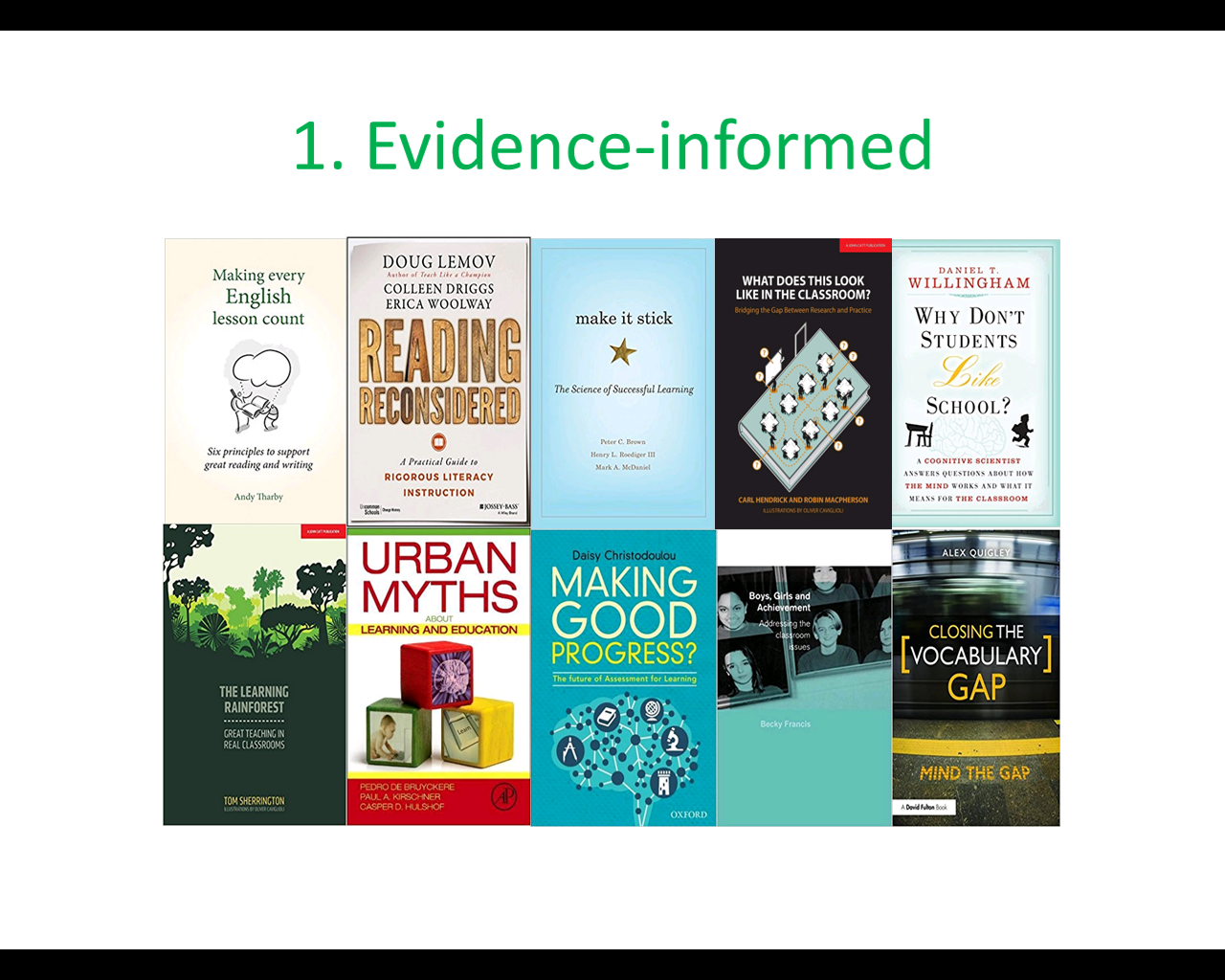

- Evidence-informed

They read a lot of stuff about teaching and learning. They want to improve as teachers, and they aren’t willing to rely on intuition to do so. I asked Erica to give me a list of the ten books they’ve read over the last few years that have been particularly influential. Here’s what she gave me:

Some of them will be very familiar to you. Some may be on your to-read or to-buy list. Others you might never have heard of.

But aren’t all departments evidence informed? you might be thinking. I don’t think so. We’re here on a Saturday morning, giving up our time because we want the answers about what might work best in teaching. We live in a bit of a bubble. Take a look at this question from TeacherTapp recently, which showed that 68% of teachers who responded still thought learning styles was a valid theory:

And Moonwater Park’s English faculty have had to plough their own furrow. Because the school’s CPD is pretty poor. They’ve sat through some seriously inadequate CPD sessions, groaning through nonsense about Bloom’s taxonomy and wincing at growth mindset banalities.

- Rigorous assessment

One book that’s had a big influence is Daisy Christodoulo’s Making Good Progress.

Like most English faculties, the new GCSE English specs caused anxiety at Moonwater Park. Grade boundaries – which are always complete guesswork anyway – are set high. The focus is on constant improvement based on clear feedback. Pupils are given grades at the end of unit assessments, but this is done with the massive caveat that grades are only set after the exams and that pupils should only focus on what is in their control i.e. getting better. The focus is therefore on avoiding complacency and emphasising consistent improvement, not obsessing over target grades and mark schemes. The numbers will take care of themselves at the end of the exam. The faculty standardise then cross-mark each end-of-unit assessments and mock exam, then each moderate their own class with queries going to Erica, the Head of Faculty. Cross-marking isn’t always popular – some teachers are keen to mark their own classes to make whole class feedback easier – but the grudging acceptance is it reduces teacher bias in marking[1]. Teachers tend to give more marks to pupils they like and mark down pupils from underperforming groups.

Another thing that they do is set papers that are slightly more challenging than the exam board specimens. This is influenced by Julia’s reading of Bjork and Bjork, and their introduction of the term ‘desirable difficulty’, where making learning harder in the short term results in improvements in long-term learning. In this case, it means that when pupils encounter the real thing, the papers are hopefully easier than expected.

And this is what Brian – one of the English teachers – when hearing of Bjork and Bjork called the practice dartboard effect. What does he mean by this?

Professional dart players practise using a special board. What’s different about this one?

Well, the trebles, doubles, 25 and bull are 50% smaller than normal match boards. This means that when they play in real games the targets seem MASSIVE. Similarly, pupils at Moonwater come out of English exams saying things like “that was much easier than the one you gave us Miss”.

Before we move on, please note that I may be the first speaker to cite a darts website (Gillings .P. (2011) http://www.dartsperformancecentre.com/dpc/blog/art/429/practice-board-investigation-.htm) as evidence at one of these events. Please don’t tell Tom Bennett; I honestly don’t think I’ll be allowed back to ResearchEd.

- A challenging Key Stage 3 curriculum

The level of challenge has also been ramped up at KS3. KS3 lead Rosemary tells me that not long ago the KS3 English curriculum was a mess. Four years ago, if you wanted to teach a KS3 lesson you needed 19 different envelopes for all the card sort resources. Lessons involved stuff like pupils acting as ‘envoys’, teaching each other pupils, generally moving around tables. KS3 lessons were taken by the most inexperienced teachers. Terminology was basic. Shakespeare was largely taught through modern ‘translations’, graphic novels and Baz Luhrman’s ubiquitous Romeo + Juliet, with guns to get the interest of the boys. The emphasis was on engagement through fun, with texts chosen for their accessibility and ‘boy-friendliness’. And now? The emphasis is on retention and retrieval of knowledge. There are lots of opportunities to practise extended writing. If you go into an English lesson you’ll usually find pupils writing in silence for 20 or 25 minutes, building up their stamina and developing their craft. This is helped by the fact that Erica has made sure that the most experienced, most skilful, most knowledgeable teachers get a hefty KS3 allocation. Technical terminology is now sophisticated, albeit with a relentless focus on effect not feature-spotting. Shakespeare is done properly, using radical ideas like using his actual language and teaching the whole thing. And Gripping but complex novels, chosen by the faculty after reading Doug Lemov’s chapter on The Five Plagues of the Developing Reader in Reading Reconsidered[2]. Now, all of the plagues are covered across KS3, ensuring pupils at Moonwater are no longer bamboozled by the step up to English GCSEs.

- Sharing knowledge

To enable a high level of challenge, Erica knows that the teachers really need to know their stuff. Why is this so important? Erica is aware that researchers have consistently found a positive link between strong subject knowledge and student gains.

As such, Moonwater’s English faculty spend a lot of time in faculty meetings working on subject knowledge. Talking about the context of novels. Annotating scripts. Discussing their interpretations of poems and threatening to kill anyone who disagrees with them. They all teach the same books, meaning they can share articles, resources and critical guides. They all teach the same topics horizontally, so Year 7 are doing Shakespeare at the same time as Year 9. The second in faculty, Julia, told me they were worried that this might get a bit tedious, a bit samey, but it didn’t. Instead there’s been lots of discussion and sharing of ideas about Shakespearean tropes, for example. It’s spread to the English office. When I was there, I got involved in a conversation about Jungian archetypes in modern Gothic fiction, a feisty discussion on allegedly misogynistic writers and listened to a fascinating impromptu lecture on equivocation in Macbeth. Unashamedly intellectual.

So what’s so special about this? Doesn’t everybody share subject knowledge in their departments? I’m not sure that they do. All English teachers have topics they feel confident teaching. Some are absolute experts in certain areas. Others have definite knowledge gaps. Some are happy to admit to this and seek assistance. I’m very happy to admit that when it comes to teaching iambic pentameter, I’m pretty shite. Others are less comfortable at saying this. Increasingly, non-subject specialists end up picking up English teaching. In this case, it’s essential that knowledge is propagated, through informal discussions and more formalised ways, such as through knowledge organisers and quality schemes of work, to ensure that all pupils receive similar opportunities to access the best insights into language and literature.

As Rob Coe[3] has argued, a key strategy for improving outcomes is ‘targeting support for teachers at particular areas where their understanding or knowledge of student misconceptions is weak’. This is what Moonwater English do: they discuss their knowledge gaps, common misconceptions and work hard to put it right. It’s not enough to know about and teach, say, the concept of the sublime. You’ll also need to be to anticipate where students might misapply it to the poetry of Wordsworth, for example.

Erica also shares blogs on subject knowledge that help teachers know more about the topics they teach. The favourite three from last year were:

- Matt Pinkett – Allusion and cultural capital[4]

- Rebecca Foster – Essay writing challenges[5]

- Sarah Barker – ‘London’ by William Blake[6]

As a result of the emphasis on subject knowledge, while they’ll be a difference in delivery, Julia tells me there’s far less likelihood that pupils in one class get less access to important facts, ideas, context and interpretations than those in another class.

- Prioritise workload

Every man, woman and their dogs seem to be banging on about workload and well-being at the moment. But, as opposed to the routine platitudes being spouted, Erica and Julia have actually taken practical steps to reduce the strain on their English staff. They’ve had to do this as they recognise that the marking expectations for English teachers are insane. I can certainly agree with this: I recently endured a dose of AQA Literature Paper 2 mock marking that nearly finished me off. One pupils, bless ‘em, wrote 24-bloody-4 pages of A4. Times that by 30 kids and it’s clearly unsustainable. Some people ask Erica why they don’t get their papers sent off to be marked elsewhere. Well, the finances don’t allow it.

So instead they’ve had to be really savvy about how they construct the English assessment calendar, particularly because the whole school assessment machine is farcical: too many data drops, badly scheduled, designed only for feeding the data beast, which has become even worse in the Frankenstein’s monster world of (reanimated) life after levels, with junk data being the order of the day.

So instead, here’s what Erica and Julia have come up with in an attempt to genuinely reduce workload in English:

- No expectations that people will mark over the weekend or during holidays, although the schedule allows this as an option for those who prefer this

- Schemes of work and end-of-unit assessments have been cut from 6 to 3 per year. As well as having fewer assessments, this means they address topics in more depth and breadth – no more madness like rushing to finish a novel for the assessment. Also, some of the assessments are now done using speaking & listening criteria and multiple choice tests, especially the ones done around the time of GCSE mock marking

- No more than 2 mock English exams in any series. They did 4 once. It wasn’t pretty

- Teachers are trained to use a combination of live marking during lessons and whole class feedback for when they need to take work home

- No emails at a weekend or after 6pm. If they need you urgently, they’ll text or call. They very rarely do

- Meetings start on time and finish on time. AOBs are not allowed. They don’t have meetings for the sake of it. Oh, and because the meetings mainly focus on subject knowledge – talking about texts and words – teachers like attending them now. They’re English teachers; this is what they signed up for

- Stationery is banned

Before you start throwing chairs and demanding Erica’s head on an A3 guillotine, let me clarify: they haven’t completely banned stationery. Just some of it. Namely highlighters and glue sticks. Why?

Rosemary told me about the impact of reading Alex Quigley’s classic blog[7], subtly entitled ‘Why I Hate Highlighters!” In it, Alex cites research that shows that highlighters:

- are ineffectual as a revision tool[8]

- feel good to use but avoid deliberate difficulty[9]

For example, when revising pupils build up a façade of confidence by highlighting text, creating a sense that they are achieving stuff and stuff is going in. Whereas tools like flashcards create deliberate difficulty by forcing pupils to test their knowledge gaps.

Rosemary also felt that highlighters:

- Waste lesson time while they’re being handed out – “Miss, this one’s gone dry. Miss, can I have a blue one instead of a pink one” etc.

But what about the glue sticks?, I hear you scream inwardly. Well, Erica read Chris Curtis’s blog ‘The Photocopier is Jammed’[10]. In it, Chris points out the problems with too much photocopying:

- Exercise books with millions of pieces of paper

- Over reliance on annotation (and highlighting – Chris doesn’t like highlighters either) of texts rather than understanding meaning

- Worksheets as a poor proxy for learning/progress – pupils might spend a lesson completing the grids on an A3 worksheet, but when you translate that to an A4 exercise book, it might only be 5 lines

Soon after, Erica had a sticky epiphany:

- We spent 400 quid on gluesticks last year – money that could have been spent on new texts

- And gluesticks waste even more lesson time than f”*^ing highlighters – where’s the lid gone? Why are you smearing that on his blazer? Why does it take 15 minutes to stick in two sheets of A4?

So, what happened when Erica refused to buy any more gluesticks?

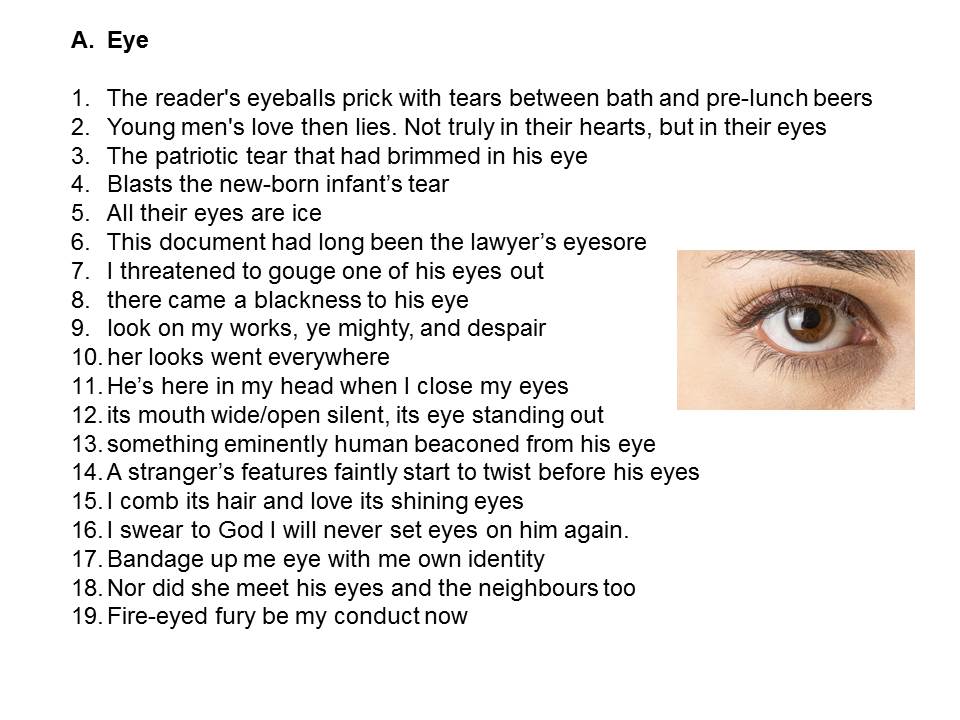

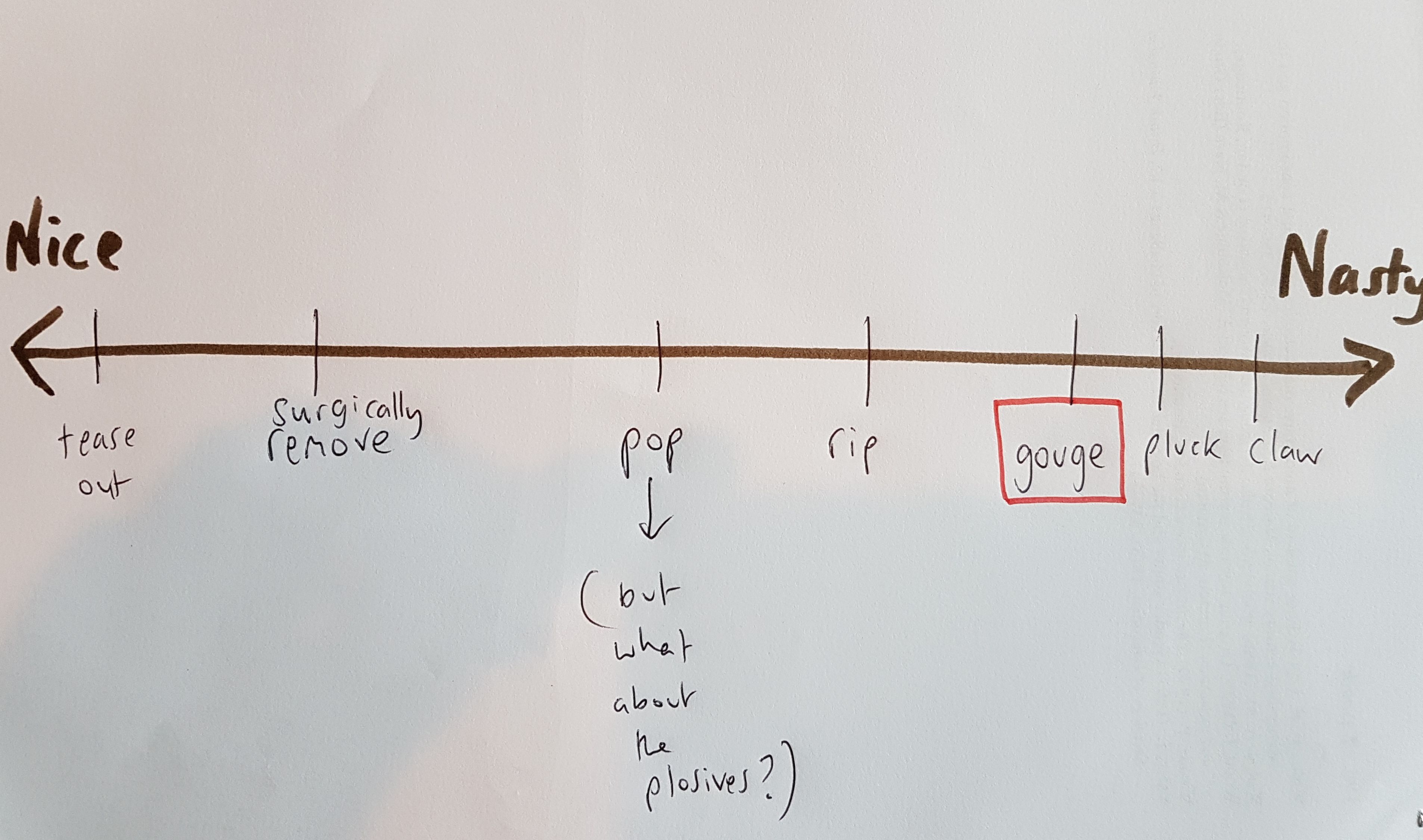

Well, at this point of the conversation, Erica’s eyes became lachrymose and her voice became hushed. She told me about the Great Stationery Riot of May 2017, where teachers at Moonwater Park fought pitched battles in the English corridors over the last box of Prittt Sticks. Where English colleagues plucked out each other’s eyeballs in a frenzied fight for the last pack of Stabilo’s finest neon chiseltips. Where children sobbed as A3 sheets sailed out of the window on a gust of the wind. Where Ofsted arrived and, appalled by the lack of half-folded, half-sticky bits of paper, put the school into special measures.

Of course, none of that took place.

Here’s what really happened:

- teachers grumbled for a bit and then noticed that kids had stuck less crap into their books that term

- Extended writing productvity soared

- Kids copied down really important stuff from the board – like teacher’s model exemplars – and ignored less important stuff

- The photocopying bill dropped by a third

- Nobody died

And like that…they were gone.

- Free of gender bias

Frequent readers of my blog or followers of my tweets will know that I’m obsessed with looking at issues around male underachievement and masculinity (I’m currently co-writing a book about this, which I’ll try and plug relentlessly at the end). If so, you might have been wondering how long it would take me to ask Erica about the English gender gap at Moonwater Park. Well, within 15 minutes Erica was admitting to me “we have a boy problem”. We have a boy/girl attainment and progress gap. Not as much as 4 or 5 years ago, when they had a boy chasm, they are closing it, but it’s still a concern.

So what have they been doing to try and change things. A key study, Julia tells me, that changed the way they looked gender was by Susan Jones and Debra Myhill[11] of Exeter University.

In this study, Jones & Myhill investigated whether teachers’ perceptions of gender affect their expectations of how pupils will do academically.

They found that teachers tend to associate girls with high academic achievement and boys with underachievement. In addition, there is a disconnect between what teachers say about boys’ potential in theory and how they act and treat boys in the practice of the classroom. Jones and Myhill revealed to Julia how boys are seen as frustrating by their teachers. They are viewed stereotypically and are labelled under a deficit model, in terms of the things they ‘cannot, will not and do not do’

Teachers’ attitudes towards behaviour show that boys and behaviour are often inextricably linked for teachers. Academic potential comes second to preconceptions about perceived behaviour problems.

Reading this, Julia and Erica realised they had an issue. They’d seen examples of teachers treating boys differently, and having lower expectations of them. They realised they needed to sit down and have difficult but frank conversations as a team.

- High expectations of all pupils

This was particularly important given Julia’s knowledge about Rosenthal and Jacobson’s classic study on the Pygmalion Effect[12] whereby teachers’ high expectations of pupils often leads to better outcomes. But Julia had also read Babad et al’s 1982 study into the opposite effect – Golem Effect – a type of self-fulfilling prophecy whereby negative attitudes about a pupil’s academic ability or potential leads inevitably to poor outcomes. And according to Babad et al. Golem beats Pygmalion every time. In other words, negative self-fulfilling prophecies has a more powerful hold over pupil’s self-efficacy than positive ones.

Since then they’ve worked tirelessly as a faculty, gently challenging each other about stereotypical language, comments that reveal potentially lower expectations and thinking carefully about their curriculum and groupings. Especially groupings.

- Equitable grouping

Moonwater’s English leadership believe that an ethos of mixed ability teaching is the fairest and most productive way to raise achievement for underperfoming groups, especially their biggest underperforming group: disadvantaged boys.

Erica had noted the link between the set that pupils are placed in and their self-efficacy in a study by Ireson and Hallam[13]. She also knew that other studies[14] have argued that lower expectations of lower sets lead to a watered down curriculum, less homework and less feedback, and have shown that pupils from certain underperforming groups are more likely to be placed in bottom sets regardless of their prior attainment.

Rosemary admitted that in the past boys who were perceived by teachers as bright but difficult were often demoted to bottom sets as a punishment for their non-compliance.

So they agreed to move to mixed ability. And behaviour and outcomes improved. With one small problem. Erica noticed that among the highest prior attainers weren’t getting as many top grades as they’d hoped. This led to a tweak in the second year: they inserted a top set in each population alongside the mixed ability groups. But even these top set weren’t your average, rigidly hierarchical top sets. They ensured that they had large percentages of higher prior attaining disadvantaged boys and other underrepresented micro cohorts in each of the top set. And that proved to be the optimum way of keeping an equitable but effective setting set-up.

- Funny, passionate, calm

They have a laugh. They take the piss out of each other in a tender and affectionate way. Some of the English teachers naturally get on better with certain of their colleagues, but there’s no cliques. If they argue, it’s usually about what’s best for the pupils.

They go out every fortnight after work. Usually to the pub, although sometimes a café as some of them don’t drink. Sometimes it’s just a very swift one, other times they’ll stay out rebelliously late.

Perhaps this is why it seems to be a stress-free faculty. It isn’t, of course. Teaching is a tough job, but any anxiety is well-disguised to avoid any stress being passed on. George, one of the NQTs, is really interested in stress contagion, having read about it in the TES and subsequently in studies[15] that show that teachers who are on the edge of burn-out pass their stress on to their pupils, even leading to lower outcomes for their pupils.

Erica recognises that the job of a head of faculty is to act as a shit-shield from above (SLT, DfE and Ofsted) and that the job of teachers is to act as a shit-shield for pupils. So they don’t panic if their class does badly, as happens from time to time, on an assessment. And they don’t provide pupils with ready made excuses to fail by complaining about the fact that they can’t take books into GCSE exams and have to actually learn stuff.

What a great faculty, eh? Having listened to these ten qualities, I’m confident you’ll agree that this is a pretty special English department.

But now is the time to reveal something which the discerning listener among you will probably have guessed already.

There is no such place as the Moonwater Park School.

That is to say, there may well be a school of that name, but I don’t know of it, nor do I know any English Faculty with just that combination of qualities. The faculty I teach in has quite a few of these characteristics. Others we’re working towards. Some of the other qualities are things I’ve read about or just feature on my own quirky wish list.

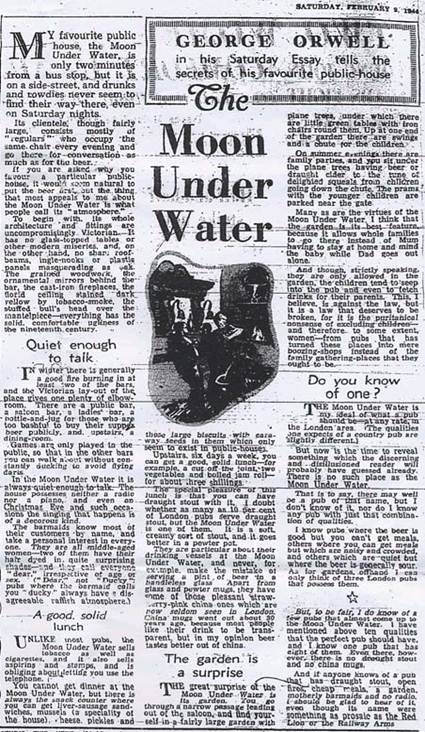

The idea for this talk was conceived after re-reading a classic essay[16] written by George Orwell for the Evening Standard in 1946. I’ve borrowed some of his words for this conclusion. In it, the great writer lists his ten essential qualities of the ideal…pub. And this mythical pub’s name? The Moon Under Water.

Let’s take a look at what George felt constituted the perfect pub:

- Victorian architecture

- Darts is only played in the public bar

- Quiet enough to talk – no radio or piano

- The barmaids know the customers by name

- It sells aspirins and stamps, and lets you use the telephone

- Snack counter selling liver-sausage sandwiches, mussels, cheese, pickles…

- Six days a week, you can get a good, solid lunch

- Creamy draught stout

- Beer is never served in a handleless glass

- The garden is its best feature – “Mum doesn’t have to stay at home and mind the baby while Dad goes out alone.”

Now some of these features of perfection seem quite dated. And quite idiosyncratic. Which reminds me of parallels with education: we often follow our personal preferences, doing what feels right. We are also vulnerable to fashionable fads.

Yet some of these features are timeless and universal. If you go into a pub these days, you’ll still want a nice drink, in a clean glass, served by someone with whom you’d like to have a friendly relationship. Just as in the classroom, in pubs relationships and quality of delivery matter. Although I’m not suggesting for one minute that you should try and persuade parents that schools should be more like pubs.

But if anyone knows of an English Faculty that is research mad, has a fun atmosphere, high expectations for all, regardless of their gender or background, likes a pint, and hates bloody glue sticks, I should be glad to hear of it, even if it is more than 7 minutes’ walk from my house like my current school.

Thanks for listening,

Mark

[1] See Christodoulou, D. (2017) Making Good Progress?: The future of Assessment for Learning

(OUP, Oxford); Campbell, T. (2015) Stereotyped at Seven? Biases in Teacher Judgement of Pupils’ Ability and Attainment, Journal of Social Policy, Volume 44, Issue 3, 517-547

[2] Lemov, D., Driggs, C. & Woolway, E, (2016) Reading Reconsidered: A Practical Guide to Rigorous Literacy Instruction (Jossey Bass, San Francisco)

[3] Coe, R et al. (2014) What makes great teaching? Review of the underpinning research, (Durham University, Sutton Trust)

[4] Pinkett, M. (2017) https://www.tes.com/news/understanding-allusion-isnt-just-about-cultural-capital-its-about-literacy

[5] Foster, R. (2017) https://thelearningprofession.wordpress.com/2017/12/16/on-our-fortnightly-essay-challenges

[6] Barker, S. (2017) https://thestableoyster.wordpress.com/2017/12/15/marks-of-weakness-marks-of-woe/

[7] Quigley, A. (2015) https://www.theconfidentteacher.com/2015/01/hate-highlighters/

[8] Dunlosky et al. (2013)

[9] Brown et al (2013)

[10] Curtis, C. (2017) http://learningfrommymistakesenglish.blogspot.com/2017/04/the-photocopier-is-jammed.html

[11] Jones, S. & Myhill, D. (2004) ‘Troublesome boys’ and ‘compliant girls’: gender identity and perceptions of achievement and underachievement, British Journal of Sociology of Education, Vol. 25, No. 5, pp. 547-561

[12] Rosenthal, R. & Jacobson, L. (1968) ‘Pygmalion in the classroom’, Urban Review, Vol. 3, Issue 1

[13] Ireson, J. & Hallam, S. (2009)

[14] Rubie-Davies, C., Hattie, J. & Hamilton, R. (2006); Hallam, S. & Parsons, S. (2013)

[15] For example, Oberle, E et al. (2016), Herman et al. (2017)

[16] Orwell, G (1946) https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/the-moon-under-water