It’s that time of year. The “revision period” is fast approaching. Around the country, students sit hunched over their bedroom desks (if they’re lucky enough to have either a bedroom or a desk), surrounded by revision guides, their notes from class and an arsenal of garishly coloured stationery. All too often, however, these study sessions splutter to a halt. They don’t know where to start. They struggle to maintain any kind of momentum. They ditch the English notes and opt to revise instead for a subject, like maths or biology, where the question of how to revise seems much more obvious.

But it needn’t be like this. There are things that we, as their English teachers, can do to stop the abrupt stalling of their study sessions. Let’s now consider ten common misconceptions about English revision and think about what we as teachers can do to help students avoid them.

- Revision is something that is done in the lead-up to exams

It’s February so revision becomes the buzzword. After-school sessions are advertised. Study skills assemblies are introduced. Revision guides and past papers are printed out. Normal homework is ditched and is replaced by a single word entry in student planners: ‘Revise!’.

All of these activities contribute to the widespread perception that revision is an activity that should be done towards the end of a course, or as an end-of-unit assessment looms. The language teachers use has a heavy influence on these mindsets, with talk of ‘catch-up sessions’ and ‘study leave’. Yet English revision should not look like this. By promoting short, frequent study sessions from the start of the course, we can help foster an attitude of ongoing “revision”, rather than last-minute cramming. Our homework should reflect this. Our Do Now tasks should reflect this. When we distribute study materials should reflect this. And above all, the language we use and the implicit messages we send to students should reflect this. 2.

2. Memorising quotes is the main focus of revision

Knowing quotes is important. But it’s not enough. Being able to recall important parts of the text, especially in closed book exams, is necessary but it’s not sufficient in itself. As English teachers, we know this. But do we make that clear repeatedly to our students?

Again, our approach sets the tone. If we mainly set quizzes about quotes we’re implying this is the be-all and end-all. Instead, we need to see this as an early stage of revision, a precursor to more generative learning activities, such as practising exploding quotes, identifying suitable synonyms, considering the specific impact of devices and so on.

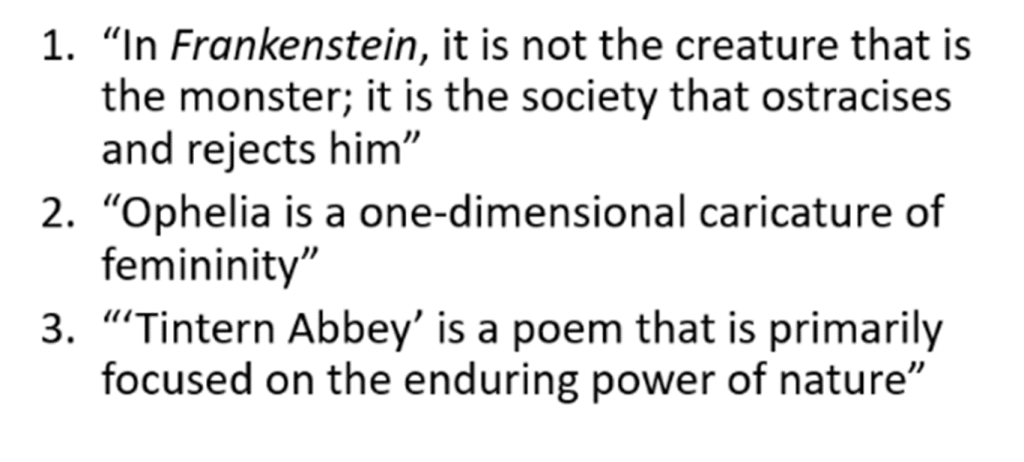

3. Retrieval practice is just for key knowledge

The ability to recall key knowledge about texts is vital. Yet, as we’ve seen, it can only be a starting point. As English teachers, therefore, it’s imperative that our retrieval activities also encourage complex, conceptual thinking. Mixed quizzing offers the opportunity to cover both aspects of successful English study. By incorporating analyse, evaluate, discuss and compare questions alongside fact-based questioning, we can encourage our students to use this foundational knowledge as a springboard for deeper thinking. Here are a few examples from A level teaching, which could be easily adapted for GCSE lessons:

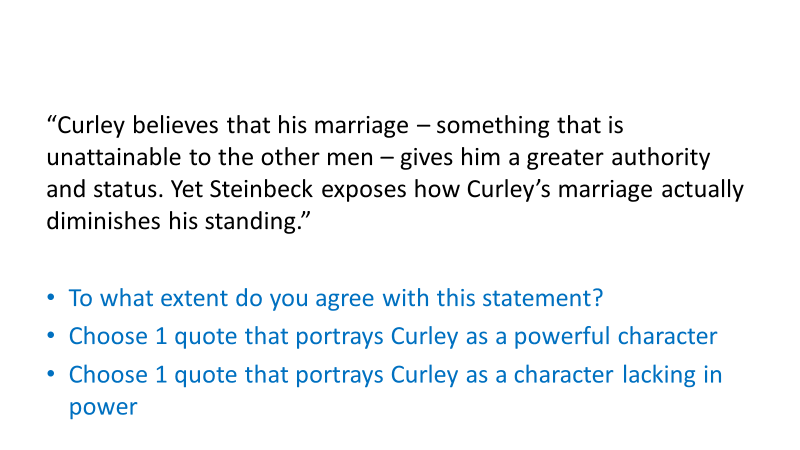

Here’s another example for Of Mice and Men:

4. Lots of notes guarantees good study sessions

Students are usually pretty rubbish at taking notes. I succeeded as an English student not because of my notes, but despite them. It wasn’t my fault though; nobody had ever shown me how to take notes. Are we making the same mistake with our students? Using the visualiser, we can model this fundamental part of the process:

This much might be obvious, but are we then checking that students understand why we annotate in this way, and how it can act as the first step of our revision process? Are we giving them useful techniques to help them organise their notes, so that they are note-taking selectively and are making useful summaries of their notes?

5. All quotes are of equal importance

Once students have memorised some ‘key quotes’ and you’ve hit them with trickier questions like the one above, they’ll hopefully recognise that, to mangle Orwell’s classic line, while all quotes are equally important, some are more equally important than others! By modelling the process and encouraging them to identify quotes with the highest utility – the ones that can cover most themes in an essay question – students will start to practise applying these quotes to different questions as part of their revision.

6. Revising context is straightforward

Read the examiners’ reports and you’ll see that students’ writing about context is a major irritant for examiners. As well as learning the basics – not mixing up Elizabethan and Victorian periods, for example – students need to be shown how to practise the skillful weaving together of contextual ideas with analysis. Getting the balance right – enough context to tick the criteria but not a mini-essay on Wordsworth’s relationship with his father – is key, and this is something they need to plan out and work on during revision.

7. If I know about the most effective study techniques I’ll be fine

So we’ve taught our students how to use flash cards. We’ve hammered home the futility of highlighting or re-reading our notes. Our work is done. We can relax now, right? Wrong. A study by Blaisman et al. found that despite knowing about the most effective study techniques, students often ended up reverting to the dodgy techniques that give the illusion of fluency, like highlighting. Disturbingly, 53% of students in this study ‘admitted to studying in a single session before an exam’. These strategies need to be revisited frequently in class, with the benefits made clear, and our homework needs to ensure that they have no choice but to use these techniques.

8. You can’t revise for the creative writing questions

While many students will happily spend time learning Macbeth quotes, far fewer will take the initiative to practise effective writing strategies. I show my students not only what good writing looks like, but also how they can learn chunks of their best paragraphs and adapt them for different exam prompts. This can give a crucial nudge to make sure that their response to the creative writing piece isn’t just dreamed up on the day.

9. If I’ve not got a good vocabulary, there’s not much I can do about it

Increasingly, I’m convinced that, like the number 42, synonyms are the answer to all questions about life and the universe. Struggling to fully analyse a key word in the quote? Synonyms. Floundering with inference? Synonyms. Can’t think of a better verb than ‘walked’? Synonyms!

But you can’t sneak a thesaurus into the exam, of course. Which is where many students struggle in English exams. They know what they want to say but can’t find the write word to say it. The answer? Learn these in advance as part of your revision. Once more, you’ll need to model this in class, explaining how belligerent and bellicose are both synonyms for ‘aggressive’ but illustrating how one works better than another in a particular context. Then it will go on a flash card as part of an exploded quote or, eventually, a full paragraph of writing.

10. Drawing up a revision timetable will make sure I revise key areas

Our students need to be organised to revise well. So giving them a timetable, with key poems to cover, characters to go over and themes to revisit seems like the obvious solution. The problems with this approach are numerous. First, different students should dedicate more time to certain activities than others, so a one-size fits all approach won’t help with this. Second, a lengthy planned out revision schedule is less easily adapted. Rather, we need to encourage our students to change the focus of their sessions depending on how these sessions are going. Monitoring and evaluating these sessions are crucial and, again, that’s something we should be modelling.

Ultimately, as experts, we can’t take for granted that students know how to study for English. The assumptions we make can mean that their revision in our subject never really gets off the ground.

If you’ve found this blog useful and haven’t already read it, you might want to get a copy of my book You Can’t Revise for GCSE English!

Many thanks for reading,

Mark