He had no chance of getting a C. In his AS exams he managed to scrape an E. His coursework, which he had spent a lot of time improving, did come out as a C grade but there was no evidence at all that he was able to reproduce that kind of standard in an exam situation. He’d barely scraped onto the A level course in the first place, having bagged a brace of Cs at GCSE. He was one of those hard-working kids that you gambled on, mainly because it would have been unfair not to recognise the effort he put in to lessons. He had little confidence in his ability in the subject and tried to keep his head down in class to avoid answering questions. So how did this pupil manage to walk away with a C grade in A level English Literature, having outscored all but two of his peers (both A* pupils) by getting a top A grade on the A2 exam?

Well, as I said, he was a real grafter: very few missed lessons, assiduous note-taker, prolific hander-in of homework. But he’d been like that for the whole of Year 12, so it wasn’t just down to work ethic. Had things just ‘clicked’ in the second year, as often happens with A level study, when the mysteries of the course suddenly seem to evaporate? Not really. He’d always understood the demands of the course – was well versed with the assessment objectives for example – yet still struggled to achieve decent marks. No something else occurred. Something that had a significant (though less dramatic) impact on his classmates: I started doing something that I’d always done with my GCSE classes, having up until that point naively assumed it was something they wouldn’t need. I simply started to spend large chunks of our lesson time sharing with the class how I approached revising for and actually answering exam essay questions.

This wasn’t just about skills, of course. Whilst allowing them to have access to the inner workings of my brain, I simultaneously bombarded them with my own knowledge, explaining how I would incorporate it into my essay responses. There’s a word for this pedagogical approach – metacognition – and when I first heard it as a buzz word about ten years ago I couldn’t work out what all the fuss was about. You see I’d always done this with my classes. What’s the point of being an expert in something, namely passing exams in a certain subject, I had reasoned, if you don’t provide insight into the best way to pass these exams? I’d pretty much had to work out for myself how to pass my exams, at school, college and uni, so why not give my pupils a leg up by letting them in on the secret of how it’s done. I’d always done this. So why the hell had I neglected to share these esoteric tidbits with my class back in Year 12?

Assumptions are dangerous in teaching and I’d made a whopping great big one. I was new to the school and my class were the product of school that was not long out of Special Measures. The Head and the stressed, often brilliant, teachers had done a sterling job of getting them out of the hole, getting a Good not long before I arrived. The pupils had been drilled for Year 11, with emergency intervention sessions and last minute revision breakfasts. They got good results but unbeknownst to me lacked specialist technical knowledge and had little clue about how to learn independently. They were mainly hopeless at revising for English and had no idea how to plan their exam strategy. I soon recognised their technical deficiencies and spent most of Year 12 beasting them on word class and sophisticated language features. But belatedly realising that they couldn’t revise or plan an essay and changed my approach everything well… changed.

Here, then, is how I teach pupils to revise and to tackle essay questions in an exam. Some of this will be bloody obvious to you. The key question though is will it be bloody obvious to your pupils?:

- You’ve got to know what quotes you’re going to use before you go into the exam. Now that is such an inane comment I feel awkward writing it. Yet I’ve seen pupils waste inordinate amounts of time trying to find quotes in exams, often not because they haven’t bothered to learn any, but because they believe that they need to find new quotes that go with this particular question. Now I know the new closed book exams seem to negate this point at GCSE, but the same point applies for the quotes they’ve memorised. If pupils believe that there are distinct quotes for each theme then they’ve got a hell of a lot more to memorise and sift through in their exams. Which leads me to:

- Pupils need to be shown that they are often pants at picking key quotes. I spend lots of time talking to pupils about why they’ve selected certain quotes. With a bit of judicious quizzing it often becomes clear that their understanding of a particular quote is poor, that they have basic vocab to use when analysing this quote and that it offers little opportunity to showcase their technical terminology or make a clear link to context. At this stage you often find that their favourite quote is in fact their mate’s favourite quote and they only picked it for that reason.

- If you’re making up your analysis on the day then you’re either a genius or an idiot. Clue: it’s invariably the latter. This again is common sense to me (and hopefully you) but to your students? Take, for example, my following list of key quotes for Mr Hyde:

- ‘like a damned juggernaut’

- ‘ape-like fury’

- ‘pale and dwarfish’

- ‘trampled calmly’

- ‘doomed to such a dreadful shipwreck, that man is not truly one but truly two’

These days, pupils obviously need to memorise the quotes. They also however benefit hugely from memorising a) language features/sentence functions/word class b) key word(s) from each quote c) juicy synonyms for each key word and d) large chunks of their best analytical paragraphs for each quote. Now you may want to argue that this is too much for some pupils. That the ones with lower ability or weaker memories will struggle with this. I argue that given enough time spent on this in lessons/as part of homework they will master this and also that these are precisely the kind of pupils who benefit most from this ‘here’s a PEA I made earlier’ approach.

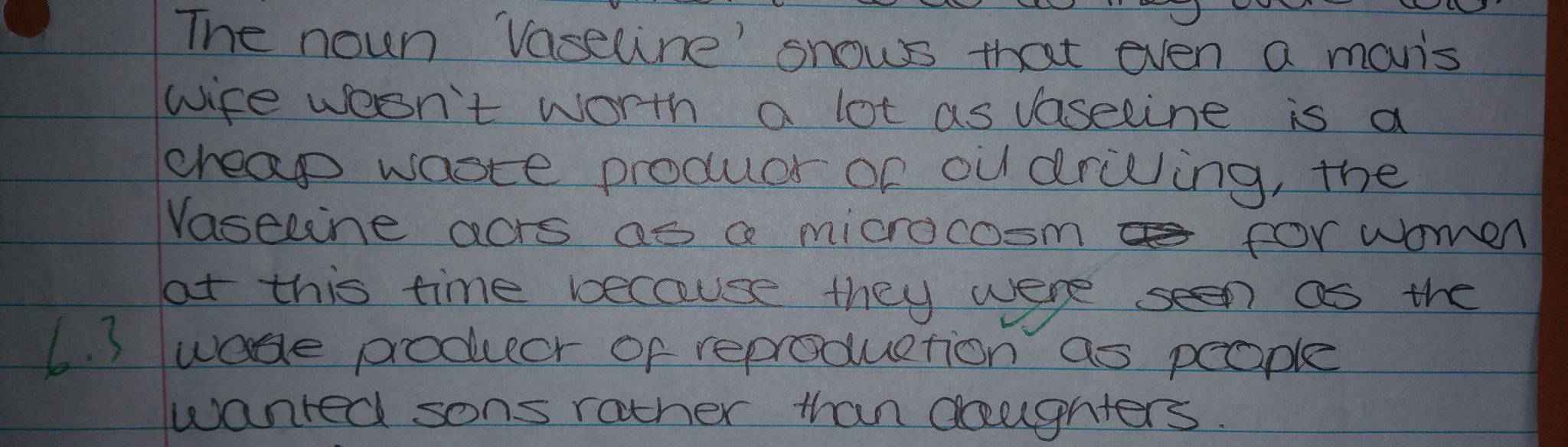

4. You have to model for pupils how they can make their highest quality sections of analysis fit just about any question. I had an exceptionally bright Year 11 pupils last year who, during an essay on Curley’s wife produced a paragraph on the ‘glove fulla vaseline’ line from Of Mice and Men. It was breathtaking in its brilliance:

I talked to her about the difference between microcosm and metonym, then insisted she memorise this chunk and put it in any essay question that came up. But what if it doesn’t fit though Sir? Ok, I said, let’s see if we can make it fit the following characters/themes:

- Relationships – yes

- Violence/cruelty/brutality – yes (see literal interpretation of quote)

- Outsiders – yes

- Role of women – obviously

- Dreams/American dream – yes

- Curley – ditto

- Curley’s wife – and again

- Slim – yes, as a contrast between how Slim talks to her

- Candy – yes, he says it

- George – his reaction to it (ironic given his misogynistic outbursts)

- Lennie – yes, his killing of her encapsulates the ‘waste product’ point

You get the point. So did she. She got full marks on the GCSE lit exam.

There’s very little that can’t be tinkered with when shoehorning in a belting quote. And even if it was tenuous, it would be a hard-hearted examiner that didn’t temporarily forget the question and give it Band 6 regardless.

5. Questions are there to be taken on. If you don’t like the wording of a question, flip it on its head. This re-framing of a question is an absolutely vital skill to make explicit. Here’s some example of how you might do this with some typical GCSE English Literature questions:

How does _______ present conflict in _____?

- Physical violence

- Psychological turmoil

- Inner conflict

- Appearance vs reality

- Past vs present

- binary opposites

- prejudice/oppression

- man vs nature

- dreams vs reality

Similarly, I’ve shown pupils how certain quotes can be used for every single one of the previous exam questions on a certain text, given that they add to our understanding of every character and theme.

With this in mind, a key skill is to get pupils to plan how they would make their list of bankers, their most impressively analysed quotes, fit into different exam questions, especially the ones that don’t seem to match.

So let’s go back to where we started: my struggling Year 13 student:

6. Have a full essay ready to reproduce on the day. Planning time should not be used for planning what you’re going to write; it should instead be used for planning how you’re going to make your essay fit the question. My Year 13 wrote at least a dozen versions of an essay (adapting and improving each time with my bits of feedback), then spent most of his revision time applying this essay to other possible questions, asking me to challenge him with trickier to adapt essay titles every week. Let me be clear: he’d done all the hard work. This was independent learning of the highest order. I’d say things like why don’t you try and apply Todorov’s narrative stages here? or your phrasing here is a bit clumsy and lacks confident vocab or are you sure that’s really litotes? and he’d go off and improve it.

Is this teaching to the test? Or lazy short cuts that allow pupils to hoodwink examiners on the day? I think not. Through sharing my insights, what I’m really doing is making them join up their learning and allowing them to see the artificial nature of the exam essay for what it is: a crude launch pad that allows pupils to show off what they’ve learnt over the course. And he had, they all had, learnt it. In a way he hadn’t previously. Each one had their own separate, utterly different pre-prepared essays etched into their consciousness and far more likely to stay there than if I’d given them a list of key quotes and told them which ones they needed to use for individual questions.

Thanks for reading,

Mark

3 thoughts on “Exam essay questions, and how to avoid answering them”